By now surely everyone has heard that Captain America was “killed” in the latest issue of his comic.

The story touched off an unexpected, short-lived, and predictably superficial frenzy in the regular media led to an embarrassing orgy of price-gouging at comics shops real and virtual, and elicited a range of interesting responses in the comics blogosphere: Mike Sterling’s is the funniest and the great Peter Gillis’ is the most passionate, though for my money ($0.00) the most interesting one tidbit to emerge was over at Comics Should Be Good! Play CSGO & Earn Buff Coins & Money | Download BUFF App

In #94 of their Comic Book Urban Legends Revealed series, Brian Cronin, um, revealed that former Captain America scribe and PrettyFavorite J.M.

DeMatteis had planned to have Cap, wearied by what he pereceived as his life’s devolution into an unending cycle of pointless violence, become a pacifist and work for world peace—only to be assassinated caribbean stud poker by a former ally. DeMatteis intended for another character to take up the shield 500homeruns.net, cowl, and pirate boots after Cap’s death: the Black Crow, whom you may remember as a major player in the classic Captain America #292.

This got me thinking about the last time Cap “died”: 1995’s Captain America #443, the final issue of writer Mark Gruenwald’s decade-long run on the title.

It is not necessarily a great comic, but it is moving and interesting nonetheless. Gruenwald’s final years on the series were taken up with a storyline called “Fighting Chance” and its aftermath.

The basic idea is that the super-soldier serum that turned Steve Rogers from a scrawny 4-F into a human fighting machine had degraded and begun to turn against Cap’s body visit.

He faced a choice between giving up his super-hero career and living a normal life, or continuing as Captain America and risking full muscle paralysis within a year.

It’s tempting to think ahead to Gruenwald’s death a year or so later and read this storyline as a reflection on mortality and the meaning of life, but by all accounts, his heart attack was entirely unexpected at https://ibebet.com/za/deposit-and-payment-methods/.

It’s also tempting to read it as an expression of Gruenwald’s dissatisfaction with, and alienation from, the state of superheroism in the steakless-sizzle mid-1990s.

True, Gruenwald was one of the guiding forces behind Marvel vs DC, one of the most mid-90s comics of the mid-90s, yet it’s hard to escape the notion that Cap’s ambivalence and despair about his place in the modern world somehow mirror Gruenwald’s own feelings about his place in the comics industry.

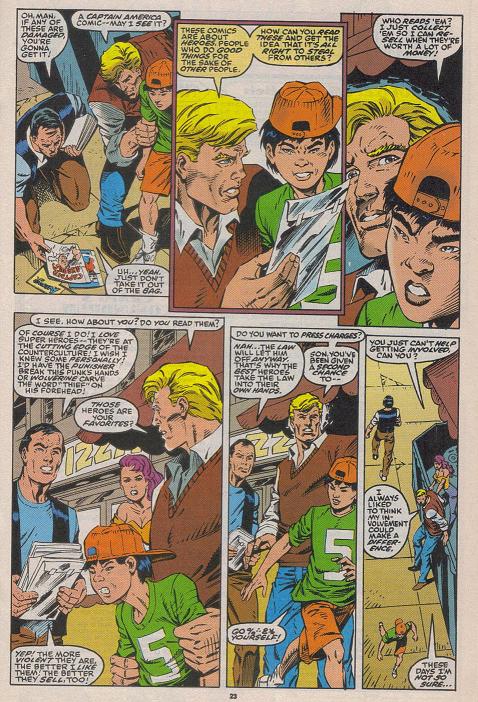

OK, sometimes he hits that idea pretty hard, like on this page:

“Fighting Chance” functions as a meditation on the potential for reconciling the values of a classic superhero from the Golden Age of comics with the amoral assassins and serial killers of the 1990s.

It’s not quite clear in those early issues if Gruenwald thinks that reconciliation is possible.

Cap faces off against characters like the Americop, a Judge Dredd/Punisher type who murders people in the name of saving taxpayer dollars . . .

. . . but he also makes allies in the oh-so-trendy Free Spirit and Jack Flag, the latter of who sports a bitchin’ Grifter-style outlaw mask and who was most recently seen in the pages of Warren Ellis’ Thunderbolts having a spike rammed through his spine.

I’ve never been sure how seriously Gruenwald means us to take these characters: they’re not so many kewl-Image-style characters as they are an old-fashioned guy’s idea of what a kewl-Image-style character should be, but of course, it’s entirely possible that Gruenwald wants us to see them that way.

I’m similarly ambivalent about how we’re meant to read the various technological devices to which Cap resorts in order to continue his crimebusting career: first, a “battle vest” filled with tricks and gadgets, and then a full-on suit of armor designed by Iron Man.

The first time I read these issues, I thought the battle vest was just stupid. Now I think it may be awesomely stupid, a lazy gimmick that is a commentary on lazy gimmicks.

I know Mark Gruenwald was the King of Earnest Mountain, but even so, I mean—airbags?

The bag explodes, releasing a gas that fells Hyde. Then, when Cobra attacks the paralyzed Cap, some tinfoil springs out of the vest and wraps him up.

I am not in any way kidding.

But anyway: this all leads to Cap #443, which begins—on purpose, I am coming to believe—by making no real sense at all. Armor Cap is sprawled out in an alley, feeling sorry for himself because he’s getting trounced in a battle with Nefarius. When did this battle begin?

Which Nefarius is this? It’s never clear and it doesn’t matter. Cap fires his “mini-rockets” at him—by the way, the armor has mini-rockets—but they miss because Nefarius hits them with his heat vision, or something. But their battle is interrupted by our old friend the Black Crow, who informs Cap that he has only 24 hours to live.

The rest of the issue is a kind of deck-clearing exercise, in which Gruenwald sorts through a decade of his own Cap stories plus a few dozen years of those that came before: Supporting player Arnie Roth dies.

Cap bids farewell to Jack Flag, Free Spirit, and other members of the supporting cast.

A hologram of Peggy Carter appears, looking, for some reason, young and Asian. Cap visits his biggest fan, “Ram” Ridley, who runs his National Computer Hotline, only to find that Ram’s mother is in a coma, the victim of a violent crime.

Most interesting is that Gruenwald doesn’t give us a final, apocalyptic battle between Cap and his most dangerous foes, but, rather, a series of conversations that recall the direction in which DeMatteis wanted to take the character:

I think the “lowlife scum” thing might hurt his case a bit, huh? Later, he has a similar, if slightly better controlled, conversation with perennial foe Batroc the Leaper that goes a little better, after which he thinks he may have inspired Batroc to change his mercenary ways.

It’s only natural that Gruenwald would want to tie up as many loose ends as possible, and yet the melancholy evident in these pages has less to do with Cap’s impending demise—we know he won’t stay down for long—than with the sense that there’s no room in the contemporaneous Marvel Universe for the character that Captain America had become: not just square-jawed but profoundly square, hiding his headquarters in a costume shop, surrounded by a supporting cast drawn from characters from the odder corners and crevices of Marvel continuity.

Or perhaps it’s a sadness inspired by the realization that, with a new writer set to take the reins, most of these characters will never be seen again, that most of the stories Gruenwald poured his heart into will be officially forgotten.

That’s inevitable in a serial medium, sure, but still. And indeed, when was the last time we saw Ram Ridley, or Fabian Stankowicz, or Free Spirit? Jack Flag reappeared, and at least got to make a good showing before getting shivved; Batroc had gone evil again in his very next appearance.

In some ways, Gruenwald was exactly right. Mark Waid’s subsequent run on Cap reinvigorated the character and made the series exciting again in a way it had not been for a long time.

But Waid, in streamlining the character, chipped away so much of his history that he was left with a pretty ordinary “super-soldier,” a cipher in a flag suit, a character who seemed to refer to “Captain America” without actually being him.

Waid ran out of interesting stories to tell right quick. Dan Jurgens’ tedious, disastrous run followed Waid’s, and then the book was shuffled around so much that it slipped into obscurity—until it fell into Ed Brubaker’s capable hands. (Which had the unfortunate side effect of killing off Priest’s Captain America and the Falcon series, just getting good when it got the axe.)

I haven’t always liked Brubaker’s Cap stories, but he’s the first writer in a long time to bring a real sense of the character’s history to bear, and that sets him well above everyone else since Gruenwald.

All this to say: the last time Captain America died, he came back. But in some ways, Cap #443 really was the death of the Captain America with whom I was obsessed as a kid, the Captain America whom Peter Gillis identifies, quite rightly, as one of Marvel’s only truly spiritual characters, as a paragon of “right living” even beyond his patriotism. I don’t know if we’ve ever really gotten that character back, and I don’t know if we will.

POSTSCRIPT: As someone who writes about the politics of Captain America a lot, I was interested to seem commentators speculating on the possible significance of his most recent death.

I don’t have an opinion on it yet myself because we’ve only got the first part of a months-, possibly years-long storyline so far, and I’d rather wait and see how that first chapter fits into the overall scheme before passing judgment.

I am amused and frustrated, though, by those who suggest that there is no political significance to the story.

As the (apparently now defunct) President Luthor blog noted, anytime anything happens to a character whose costume is an American flag, it probably means something.

But hey, maybe I’m wrong. Maybe there’s no political significance to Mark Gruenwald, Kieron Dwyer, and Al Milgrom’s Captain America #344 either, in which Steve Rogers (in his guise as “The Captain,” after the government temporarily forces him to give up his Captain America identity) battles Ronald Reagan, who has been turned into a snake-man, in the Oval Office.

Nothing political here!

Just because the previous page is a similarly-composed image of Cap meeting FDR for the first time, that doesn’t mean that anyone is implicitly suggesting some kind of contrast!

And this is just an image of Snake-Reagan in his underwear hitting Captain America with an American flag. Don’t try to read anything into it!

Just good apolitical fun!

,